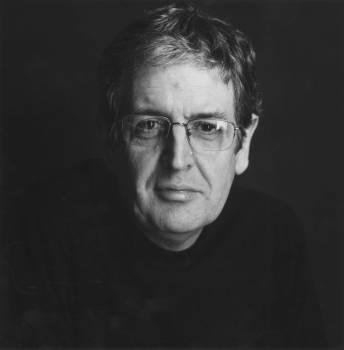

Michael Fisher writes: It was sad to learn of the death at his home in Dún Laoghaire on Wednesday 29th May of another Carleton scholar, the poet & TCD Professor emeritus Gerald Dawe. I met him a few years ago during the East Side arts festival at his former school in East Belfast, Orangefield Boys Secondary (where Van Morrison was also a pupil).

His MA thesis at University College Galway in 1977 was entitled: “A critical study of the major works of William Carleton (1794-1869)”. He was also a contributor at the Society’s summer schools. He was 72, and in checking his biography I now realise we shared the same birthday on April 22nd 1952. May he rest in peace. I published this article about him in April 2015 following our meeting in Belfast:

Gerald Dawe: The Stoic Man

06/04/2015 BY BORDERROAMER

Professor Gerald Dawe, Director of the Oscar Wilde School of Irish Writing at TCD, returned to Orangefield School in East Belfast in August 2014 as part of the East Side Arts Festival. During his talk another former pupil looked in the door and stood at the back for a while, before going on to perform in concert: Van Morrison. During his talk Professor Dawe mentioned that he had been a postgraduate student at University College Galway, where he completed an MA thesis on William Carleton. He was a contributor to the William Carleton Society International Summer School in 1994 and 2008. He has now published a new collection of essays and memoirs, ‘The Stoic Man’ (Lagan Press). In The Irish Times, he writes about the publication:

‘The Belfast I left behind doesn’t exist anymore’

Gerald Dawe – Irish Times Monday April 6th 2015

In the autumn of 1974 as a 22-year-old, I took the Ulsterbus to Monaghan town, and from there boarded the CIE coach that wound its way through several counties before arriving at Eamonn Ceannt Station off Eyre Square in Galway. It was a little over 40 years ago. The Belfast I had left behind doesn’t exist anymore, except in people’s minds and memories. The republic I was travelling through has also been transformed, including the somewhat sleepy market town that was Galway.

How can one ever remember the tone and timbre of the 1970s and the values of the republic that really were on the cusp of lasting change? It was a different world, for sure, but some things remain lodged in the memory of that time. Like the grotesque disfiguring violence inflicted upon ordinary people by the paramilitaries; like the long and arduous battle women of all classes and backgrounds had to endure to achieve basic civil liberties in their own country; like the demeaning deference expected by a male-possessed Church and the preening patronising of many (male) politicians.

But I also have a lasting sense of the edgy, challenging focus of the culture that was calmly self-confident and productive of counter images and contrary views.

I have no nostalgia for that time, although in The Stoic Man, the new collection of essays and memoirs I have just published with Lagan Press, the recalling of life in the west of Ireland in the 70s sounds again like a “sheltering place” from the travails and troubles of the Belfast I had in part left behind. So The Stoic Man is accompanied by a collection of Early Poems written during those years in Galway’s old city, around the streets and canal-ways, the bridges, Lough shore and harbour where we used to live.

It is hard to think of how things could have been so different without making it seem as if things turned out not as well as one had hoped, which is not the case. The fact is though that no one back then that I knew really planned a future. It sort of just happened. Maybe that is the biggest change I can spot between then and now.

Targets, outcomes, graphs and statistics, the numerical volumes of which we seem to be increasingly addicted in post-“Celtic Tiger” Ireland, forecasting everything from weather to economic predictions to just about every facet of social life. These strainings after certainty certainly did not exist. We lived more in the moment. That may have been unwise, I don’t know, but what I can say is that the not knowing about these matters did not halt our growth or stunt our enthusiasm for life.

The petulance, complaint and unceasing quest for factoids and percentages, faults and failings, blame and admonishment which characterises so much of Irish life today did not play any significant part in our life back then, or if it did it hasn’t left any trace behind in my memory. Politics was cut and thrust; business was precisely that, business: nothing more, nothing less but nothing like the current fad for elevating it to a new religion.

There was an intelligent debate going on about literature and art, among many other things, that weren’t in hock to the market-place or the mantra of economy. Perhaps, surprisingly too, there was an openness and appetite in brashly engaging with European ideals, probably because we had only recently joined the European family. This act would prove critical in underpinning the modernisation of our infrastructure like roads, and the liberalisation of our codes of conduct. But also, critically, the opening of our minds as well; no longer being obsessed with England started to take root sometime around the 70s.

The Stoic Man sorts some of these bass notes into a record of personal time. From growing up in a vibrant 60s Belfast, through the blunt decades that at times followed, before the republic soared economically and then crashed unceremoniously leaving the ordinary “Joe” to pick up the tab.

And now what? The book ends with a few more questions than it can possibly answer.

I hope The Stoic Man is a good read, alongside those Early Poems written by a young lad who I kind of remember disembarking from the dewy CIE coach one crisp late afternoon many moons ago.

MEMORY

in memory of Bridget O’Toole

It is a desert of rock

the rain has finally withered

till we are left black

dots on a shrinking island.

We come like pilgrims

wandering at night through

the dim landscape. A blue

horizon lurks behind whin

bushes and narrows to pass

the pitch-black valley.

We are at home. A place as

man-forsaken as this must

carry like the trees a silent

immaculate history. Stones

shift under the cliff’s shadow.

Nearby the tide closes in,

master of the forgotten thing.

GERALD DAWE (from http://www.ricorso.net)

| 1952- [Gerald Chartres Dawe; fam. “Gerry”]; b. N. Belfast; ed. Orangefield Boys School (‘an extraordinary school’), East Belfast; worked with Sam McCreadt at Lyric Youth Th.; grad. NUU (Coleraine), BA., 1974; briefly worked at Central Public Library, Belfast; held major state award for research, 1974-77; wrote a thesis on William Carleton under Lorna Reynolds, Galway, MA 1978; lecturer, UCG [1976]; appt. lect. in English and Drama, TCD, 1988; introduced to Padraic Fiacc by Brendan Hamill, 1973; Arts Council Bursary for poetry, 1980; Macauley Fellowship for Literature, 1984; taught at Galway University, 1977-1986; m. Dorothy Melvin; a dg., Olwen, b. 1981; also a son, Iarla; appt. lect in English, TCD, 1988; moved to Dublin, settling in Dun Laoghaire, 1992; |

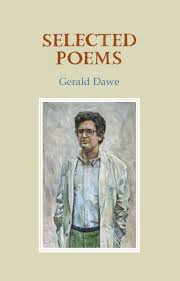

| Poems: Sheltering Places (1978) and The Lundys Letter (1985), winner of Macaulay Prize [Fellowship in Literature]; fnd. ed. Krino; ed. with Edna Longley, Across the Roaring Hill: The Protestant Imagination in Modern Ireland (1985) and The Younger Irish Poets (1982, reissued 1991); criticism includes How’s the Poetry Going? (1991), False Faces (1994), and Against Piety: Essays in Irish Poetry (1995); Director of the Oscar Wilde Centre for Irish Writing (TCD); issued The Rest is History (1998), dealing with influence of Belfast culture on Van Morrison and Stewart Parker; issued Lake Geneva (2003), poems; appt. TCD Fellow, 2004; his Collected Criticism was edited by Nicholas Allen in 2007; |

| Has taught at Boston College and Villanova Univ.; issued Points West (2008), poems, his seventh collection; issued an anthology of Irish poetry of WWI (Earth Whispering, 2009); presents RTE poetry Programme [Sats.]; directs the Oscar Wilde Centre for Irish Writing; gives a talk entitled “From Ginger Man and Borstal Boy to Kitty Stobling: A Brief Look Back at the Fifties”, concluding a public lecture-series on that decade at TCD, March 2011; his wife Dorothea is head of Public Affairs at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. |

| Poetry |

| Heritages (Breakish: Aquila/Wayzgoose Press 1976), [20]pp. [also signed ltd. edn. of 25];Blood and Moon (Belfast: Lagan Press 1976) [16pp.; pamph.];Sheltering Places (Belfast: Blackstaff 1978);Dead Loss [Poetry Ireland Poems, No. 9] (Portmarnock: Poetry Ireland 1979) [ 1 sht.; signed copy, TCD Library];The Lundys Letter (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 1985), 49pp.;The Water Table (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman 1991), [6], 18pp.;Sunday School (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 1991), 47pp.;Heart of Hearts (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 1995), 47pp.;The Morning Train (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 1999), 51pp.;Lake Geneva (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 2003), 56pp.;Points West (Oldcastle: Gallery Press), 56pp. |

| Criticism |

| ‘An Absence of Influence, Three Modernist Poets’, in Tradition and Influence in Anglo-Irish Poetry, ed. Terence Brown & Nicholas Greene (London 1989), pp.119-42;How’s the Poetry Going? (Belfast: Lagan Press 1991) [review essays];A Real Life Elsewhere (Belfast: Lagan Press 1993) 112pp. [essay];False Faces: Essays on Poetry, Politics and Place (Belfast Lagan Press 1994), 104pp.;Against Piety: Essays on Irish Poetry (Belfast: Lagan Press 1995), 193pp. [12 essays];The Rest is History (Newry: Abbey Press 1998), 123pp.;Stray Dogs and Dark Horses: Selected Essays on Irish Writing and Criticism (Newry: Abbey Press 2000), 212pp. [includes essay on William Carleton];The Proper Word: Collected Criticism – Ireland, Poetry, Politics, ed. Nicholas Allen (Creighton UP 2007), 365pp. |

| Miscellaneous |

| ed., with Edna Longley, Across the Roaring Hill: The Protestant Imagination in Modern Ireland (Belfast: Blackstaff 1985), xviii, 242pp.intro., Faces in a Bookshop: Irish Literary Portraits (Galway: Kennys’ Bookshop 1990), 163pp. [marking 50th Anniversary of Kennys];ed., with John Wilson Foster, The Poet’s Place – Ulster Literature and Society: Essays in Honour of John Hewitt, 1907-87 (Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies 1991), xi, 330pp.;ed., Yeats: The Poems (Dublin: Anna Livia 1993), 160pp.;intro., Literature in Ireland: Studies in Irish and Anglo-Irish [1916] by Thomas MacDonagh (Nenagh, Co. Tipperary: Relay Books 1996) [with profile by Nancy Murphy], xiv, 209pp. |

| Edited anthologies |

| ed., The Younger Irish Poets (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1982), and Do. [reiss. as] The New Younger Irish Poets (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1991), xv, 176pp.ed., Catching the Light: Views and Interviews (Moher: Salmon Press 2008), 184pp.ed., with Jonathan Williams, Krino 1986-1996: An Anthology of Irish Writing (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1996), 435pp. incl. 80 writers; critical essays by Susan Schriebman, Hugh Haughton; J. C. C. Mays; Eavan Boland; Nuala Ni Dhomnaill; Terence Brown; Henry Gifford; Eoin Bourke also stories by John McGahern; Peter Hollywood];ed., with Michael Mulreany, The Ogham Stone: An Anthology of Contemporary Ireland (Dublin: IPA 2001), x, 230pp., ill., ports.;ed., Earth Voices Whispering: An Anthology of Irish War Poetry (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 2009), xx, 412pp. [incls. as Postscript Samuel Beckett’s “Capital of the Ruins”]ed., Conversations: Poets & Poetry (q. pub. 2011). |

| Contributions |

| ‘Checkpoints: The Younger Irish Poets’, in Crane Bag, 6, 1 (1983), pp.85-89;‘Where Literature Ends and Politics Begins’, in The Linen Hall Review, 5, 3 (1988), cp.26;‘Brief Confrontations: Convention as Conservatism in Modern Irish Poetry’, in Crane Bag, 7, 2 (1983), pp.143-47;‘A Question of Imagination: Poetry in Ireland Today’, in Cultural Contexts and Literary Idioms in Contemporary Irish Literature, ed. Michael Keneally (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1988)‘Living in Our Time’ [review], in Linen Hall Review (Summer 1990), pp.42-3;“Three Poems” [‘Herald’; ‘Heart of Hearts’; ‘Couplet’] in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 17, 2 (Dec. 1991), p.103;interview with W. J. McCormack/Hugh Maxton, Linenhall Review (Spring 1994), pp.14-16;‘Visiting Chartres’, in Fortnight (Nov. 1994), 32-33 [taking issue with Ronan Bennett’s ‘An Irish Answer’ in the Guardian, Mary Holland, and others, ‘a key feature of Protestantism is precisely its intense individualism and reluctance to nominate itself, or to be exploited, as representative’];‘Parts of Speech’, in Fortnight Review (May 1995), p.38 [an account of his experience and views of the Irish language and politics relating to same];‘Praising the Poet’, in Fortnight Review, 344 (Nov. 1995), p.22-23;‘Civil Codes’ in Fortnight Review (March 1996), pp.26-27) [with cheerful phot. ill.; writing on Ireland and Czechoslovakia];‘Finding the Language: Poetry, Belfast, and the Past’, New Hibernia Review, 1, 1 (Spring 1997), pp.9-18;‘Small is Beautiful’, in Fortnight (July-Aug. 1997), p.26;‘Bring it all back home’, in Fortnight (Jan. 1999) [review of Michael Longley, Selected Poems and Broken Dishes; Denis Sampson, The Chamelion Novelist: Brian Moore];“Raccoons” [a poem], in The Irish Times (10 May 2003), Weekend, p.10;“Midsummer Report” and “The Interface” [two poems], in Fortnight (April 2003), p.31; ‘Francis Ledwidge: A Man of His Time’, in The Irish Times (31 July 2004), p.11 [extract from a lecture given at Slane, Sunday 25th July 2004; see under Ledwidge];Foreword to Facing White: A Collection of New Writing from the Oscar Wilde Centre M Phil in Creative Writing [TCD] (Lemon Soap Press 2007).Review of The Red Sweet Wine of Youth, by Nicholas Murray [on British Poets of WWI], in The Irish Times (12 March 2011) [Weekend Review].Review of Now All Roads Lead to France: The Last Years of Edward Thomas, by Matthew Hollis, in The Irish Times (13 Aug. 2011), Weekend Review, p.10. |

| See also Graph, No. 1 (Sept. 1995), & No. 2 (March 1996). Also extensive contributions to The Honest Ulsterman, issues 57-97 (see Tom Clyde, ed., Honest Ulsterman, Author Index, 1995). |

| Bibliographical details: Across the Roaring Hill: The Protestant Imagination in Modern Ireland: Essays in Honour of John Hewitt, ed. Gerald Dawe & Edna Longley (Belfast: Blackstaff 1985), xviii, 242pp.; contains essays, James Simmons, ‘The Recipe for All Misfortunes, Courage’ [on Joyce Cary, S. H. Bell, Forrest Reid], pp.79-98; Michael Allen, ‘Notes on Sex in Beckett’, pp.25-38; W. J. McCormack, ‘The Protestant Strain: A Short History of Anglo-Irish Literature from S. T. Coleridge to Thomas Mann, pp.48-78; Edna Longley, ‘Louis MacNeice, The Walls are Flowing’, pp.99-123; Bridget O’Toole, ‘Three Writers and the Big House, Elizabeth Bowen, Molly Keane, Jennifer Johnston’, pp.124-38; J. W. Foster, ‘The Dissidence of Dissent, John Hewitt and W. R. Rodgers’, pp.161-81; Terence Brown, ‘Poets and Patrimony, Richard Murphy and James Simmons’, pp.182-95; Lynda Henderson, ‘Transcendence and Imagination in Contemporary Ulster Drama, pp.196-217; Dawe, ‘Icon and Lares, Derek Mahon and Michael Longley’, pp.196-217. The title of the collection derives from a poem by John Hewitt (‘across the roaring hill … our indigenous Irish din’). [See Table of Contents in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Editions”.] |

| Against Piety: Essays in Irish Poetry (Belfast: Lagan Press 1995), 193pp.; Brief Confrontations: The Irish Writer’s History [19]; A Question of Imagination: Poetry in Ireland [31]; An Absence of Influence: Three Modernist Poets [45]; Heroic Heart: Charles Donnelly [65]; Anatomist of Melancholia: Louis MacNeice [81]; Against Piety: John Hewitt [89]; Our Secret Being: Padraic Fiacc [105]; Blood and Family: Thomas Kinsella [113]; Invocation of Powers: John Montague [127]; Breathing Spaces: Brendan Kennelly [145]; Icon and Lares: Michael Longley and Derek Mahon [153]; The Suburban Night: Eavan Boland, Paul Durcan and Thomas McCarthy [169]. |

| The New Younger Irish Poets, ed. Gerald Dawe (Belfast: Blackstaff 1982; revised edition 1991); contains poems by Thomas McCarthy; Denis O’Driscoll; Julie O’Callaghan; Rita Ann Higgins; Sebastian Barry; Aidan Carl Matthews; Sean Dunne; Mairead Byrne; Michael O’Loughlin; Brendan Cleary; Dermot Bolger; Peter Sirr; Andrew Elliott; John Hughes; Peter McDonald; Patrick Ramsay; Pat Boran; Kevin Smith; Martin Mooney; John Kelly; Sara Berkeley; also biographical and bibliographical notes; select bibliography; poetry publishers; acknowledgements; index of first lines. [Ulster poets are Martin Mooney; Peter McDonald; John Kelly; John Hughes; Andrew Elliot; Brendan Cleary.] |